Like many expatriates in Hong Kong, Madeline Bardin is thinking more and more about leaving.

The 36-year-old entrepreneur has thrived in the city for seven years, but she worries that its summer of unrest isn’t going away anytime soon. She won’t go outside with her 8-month-old son without first checking chat groups and the news for reports of tear gas, and she recently cancelled a business trip on concern that protests at the airport might prevent her from returning home.

“We have a young family to think about and we think this is just the beginning of the changes in Hong Kong,” said Bardin, who moved to the city from London in 2012. “Long term, it just doesn’t make sense for us to stay here with the rising instability.”

Hong Kong’s ability to assimilate people from around the globe has helped turn the former British colony into one of the world’s biggest financial and commercial hubs. But that status is increasingly under threat as expats and their employers weigh the costs of committing to a city mired in its worst political crisis since the handover to China in 1997.

If people like Bardin decide to leave, it could do significant damage to an economy that hosts the world’s fourth-biggest stock market and regional offices for hundreds of foreign companies.

Fitch Ratings cited Hong Kong’s deteriorating international reputation as one reason for downgrading the city’s credit rating on Friday, saying that public discontent is likely to persist even after Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam withdrew the controversial extradition bill that first sparked the demonstrations three months ago.

Just a few hours after the Fitch statement on Friday, police used tear gas in a populated area to disperse protesters who dismantled traffic lights and started fires. On Saturday, protesters blocked a main road in Mong Kok, a busy shopping and residential district, and burned a barricade near the police station before being chased off by hundreds of riot cops.

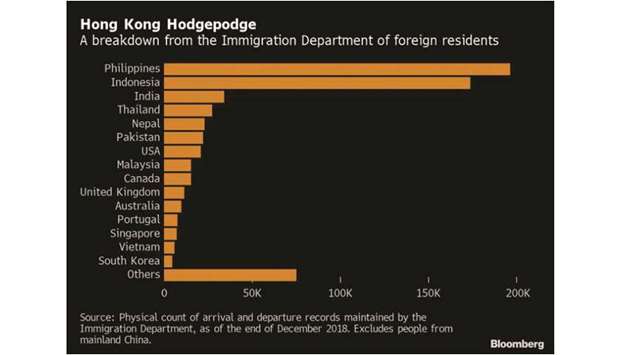

Hong Kong has long attracted international bankers, lawyers and other professionals with its energetic urban lifestyle, negligible crime rate and low taxes – a combination that convinced expats to stomach sky-high rents and cramped living spaces. At the end of 2018, the territory had more than 650,000 foreign residents, in addition to the more than 1mn people from mainland China who have settled in the city of 7.5mn since 1997. While Hong Kong’s government doesn’t publish comprehensive immigration statistics frequently enough to gauge the full impact of this year’s unrest, there are signs that foreigners are cooling on the city.

Applications for general employment visas dropped 7% in August from a year earlier, after rising on an annual basis for most of 2019, according to official figures. The number of mobile residents – those who recently spent between one and three months in the city – fell 4.1% in the first half, the biggest decline in a decade.

Online forums now often feature expats debating whether to leave Hong Kong to give birth, whether it’s safe to let their kids take mass transportation, and whether to move out of the city for good. Many worry that Beijing is chipping away at the “one country, two systems” framework that gives Hong Kong certain freedoms unavailable in Communist China. The extradition bill would have exposed both Hong Kongers and foreigners to the risk of being sent to the mainland to face what the US State Department has called China’s “capricious” legal system.

Hong Kong’s status as “Asia’s World City” was based on “values that are eroding quickly as Beijing exerts more and more influence in Hong Kong, especially in recent years,” said Lo Kin-hei, vice chairman of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party. “If these values are gone, those names and status Hong Kong enjoys now will be gone forever.”

For all its challenges, Hong Kong has plenty of foreigners committed to the city for the long haul. Some argue that the turmoil has had minimal impact on their day-to-day lives and that Hong Kong will weather the storm just as it did during Asia’s financial meltdown in the late 1990s and the SARS outbreak in 2003.

Several foreigners have been notable fixtures at the demonstrations, offering support to protesters, live-streaming clashes with police on Twitter, and in at least one case drawing the ire of pro-Beijing lawmakers.

Others are reluctant to leave for economic reasons. In a survey of 982 Filipino domestic helpers conducted by HelperChoice, a recruitment platform, 45% said they were worried about the protests but not enough to leave Hong Kong, where salaries are often far higher than in their home country.