When researchers in Los Alamos published a study last month revealing the emergence of a mutant coronavirus strain, a finding buried deep inside alarmed Robert Gallo, one of the co-discoverers of HIV.

The mutation of the coronavirus’s outer spikes could help the virus escape the grasp of otherwise neutralising antibodies and “make individuals susceptible to a second infection,” the study warned.

“They saw recombinant forms, and those are scary,” Gallo, co-founder and director of the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and co-founder and international scientific adviser of the Global Virus Network, said in an interview. “The structure of the spike has features reminiscent of HIV’s spike protein.”

The ability of the novel coronavirus to mutate, and possibly to infect individuals with multiple strains at once, is the latest complicating factor in the scientific race to understand protective immunity to the pandemic disease.

Identifying that immunity — both by recovering from the disease and through producing a vaccine — will be the single most important scientific development over the course of the pandemic.

It would allow Americans the comfort of knowing that they are protected and businesses the confidence to bring employees back to work. It would provide local, state and federal governments with an efficient testing tool that could get the economy moving again.

But the world’s leading scientists working to solve it are throwing cold water on the prospect that antibody testing will be the tool that can achieve any of those goals anytime soon, saying a much longer timeframe for research is required.

It is a reality that has been aggressively challenged by lawmakers and Trump administration officials eager to rush out a vaccine within the year and deploy antibody testing as a barometer for workforce safety.

Scientists say that, with merely five months of data collected on the new virus, it is impossible to determine with high confidence whether those who have survived Covid-19 once are naturally protected from a second infection.

The best antibody tests available today are able to tell individuals whether they have been exposed to the virus — not whether the antibodies that were produced during their infection mean they are protected from getting ill from the virus again.

Scientists investigating the question of immunity have yet to determine the prevalence of antibodies that “neutralise” the virus from spreading within the body. They don’t yet know whether those antibodies will work in safeguarding against reinfection, nor how many would be required to guarantee protection. They cannot yet say whether virus mutations and multiple strain infections will allow the virus to circumvent those antibodies.

To answer these questions, they insist there is no substitute for extensive studies — the type of research that typically takes years. And only with that knowledge will they be able to declare that acquired immunity, or a vaccine, provides durable, long-term protection.

“There isn’t enough time. It’ll take the bulk of a year before we see a correlate for protection,” said Gallo. “There’s still more to the immune system than we understand — in terms of correlate of protection, it’s not always there.”

Not all antibodies are equal

When the body’s immune system reacts to an infection, antibodies respond by attacking all different parts of the invading virus.

If the spiked surface of the coronavirus evokes a crown, then scientists are targeting a single jewel on its bedazzled surface — an isolated area of one protein, known as the receptor binding domain, or RBD.

Antibodies that inhibit those receptors are the best hope of virologists seeking to prevent the coronavirus from binding to human cells, said Mike Feldman, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

“These are the most likely antibodies that will have neutralising effects,” Feldman said, cautioning that the RBD molecules had not yet been proven to neutralise the virus.

“Everyone’s going into their vaccines with this RBD molecule,” he added. “Right now, the money and the thinking is that this RBD molecule is the really critical piece.”

Antibody tests that were rolled out to the public in April and May, approved by the Food and Drug Administration, can determine if an individual has been exposed to the virus, but cannot yet determine the presence of antibodies that are equipped to stop future infectious spread.

Those tests detect the presence of antibodies responding to nucleocapsids — a viral shell protein. They do not necessarily identify the presence of RBD antibodies, which may ultimately prove protective against reinfection.

“The challenge becomes making an assay that measures the antibodies that correlate with neutralising the virus and preventing infections. That sounds really easy. It is not,” Feldman said, referring to tests. “This is one of the really, really active areas of research. People are trying.”

The discovery of neutralising RBD antibodies to the coronavirus provided some optimism among scientists that survivors could, theoretically, enjoy natural immunity.

But mutations in the virus complicate that theory, and several other critical questions remain unanswered.

The amount of neutralising antibodies that would be required in the body to prevent reinfection remains unknown.

The history of other coronaviruses, including those that cause the common cold, also suggests that any level of immunity after recovery might not last long.

“One of the things that gives people pause is that the other coronaviruses — of the colds we get, some of them are caused by coronaviruses — the immunity conferred by that infection is not particularly durable,” said Alan Wright, the chief medical officer at Roche Diagnostics, one of the primary producers of diagnostic and antibody tests for the coronavirus in the United States.

“There are a group of people who have been initially infected with that group of coronaviruses who have a weakening immunity and have been infected by the same virus later in life,” he said.

Within a matter of weeks, he said, Roche expects to complete critical work on neutralising antibodies that could provide his team the ability to equip its tests with the capacity to detect RBD antibodies.

“But then the next piece that we need — and there’s no replacement for this — is to have people that have been exposed to the disease that have a defined immune status — that we can define their immune status — then re-exposed to the disease, and then they don’t become ill,” Wright said.

That prospective model, of identifying, enrolling and following trial candidates over an extended period of time, is an irreplaceable process that usually takes years, Wright said. In the interim, an eight-week-long study, a six-month-long study or a yearlong study will at best be able to determine immunity for the length of time of the study itself.

“It is disappointing, certainly, to think about having to follow this out for years — and that is the most definitive way to declare immunity, with these prospective trials,” he said. “The push to define this immunity, as you might imagine, is significant.”

Public pressure

Maskless and frustrated, Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky turned to a camera in a cavernous Senate hearing room on Tuesday and asked Dr Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert then self-isolating in his home, for a definitive statement.

“The question of immunity is linked to health policy, in that workers who have gained immunity can be a strong part of our economic recovery,” Paul said. “You’ve stated publicly that you’d bet it all that survivors of coronavirus have some form of immunity. Can you help set the record straight that the scientific record, as is being accumulated, is supportive that infection with coronavirus likely leads to some form of immunity?”

Fauci’s answer was nuanced. Basic immunology, and decades of studying other similarly structured viruses, strongly suggests that antibodies provide some level of protection against reinfection from Covid-19. But what remains unknown, he said, is the degree of antibodies needed to give an individual long-lasting protection.

“I think it’s in the semantics of how this is expressed,” Fauci said. “You could make a reasonable assumption that it will be protective. But natural history studies over a period of months or years will tell you definitively if that’s the case.”

Over the past two months, the FDA has approved 12 serology tests designed to detect the general presence of antibodies in those who have recovered from the coronavirus. FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said repeatedly throughout April that antibody tests are “one piece of the larger response that you’ve heard in the America Returning to Work plan” developed by President Donald Trump and the White House coronavirus task force.

“While these are just one part of our larger response effort, they can play a role in helping move our economy forward by helping healthcare professionals identify those who have immunity to the Covid-19,” Hahn said at a White House press briefing on April 24.

That message is slowly changing. This week, the White House said that antibody testing would “enhance our coronavirus monitoring efforts” — an indication the tests would not, for now, be used by the administration as a screening mechanism for Americans hoping to go back to work.

One White House official said the administration is still “learning what these tests mean as we move forward,” noting that the federal government has sponsored a pilot programme studying previously infected individuals in Detroit and New York City.

“Over 120,000 serology tests will be done on hospital workers and first responders to get a good idea of what the experience has been with different infections,” the senior administration official said.

What they learn will be key not only to developing confidence in an individual’s natural immunity to the virus, but also to the development of a vaccine.

Gallo, who developed the first antibody test for HIV, said the most likely and most effective course of action would be to pursue an interim vaccine requiring intermittent boosters — at least until a more durable vaccine is identified.

“This is a unique opportunity to learn more about the innate immune system,” Gallo said. — McClatchy Washington Bureau/TNS

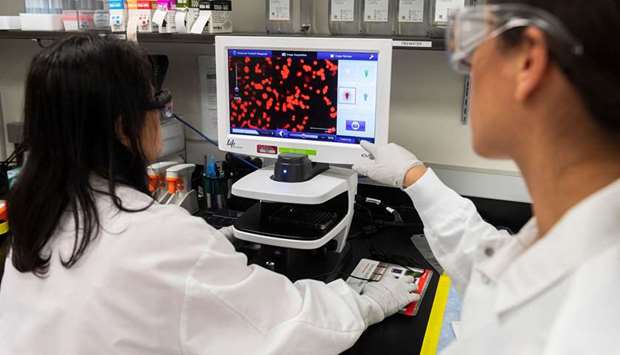

INSPECTION: Dr Sonia Macieiewski, right, and Dr Nita Patel, Director of Antibody discovery and Vaccine development, look at a sample of a respiratory virus at Novavax labs in Rockville, Maryland.