For years, low inflation looked like a classic rich-world problem. Plenty of developing economies now have some version of it too.

Central banks have responded like their developed-country peers: by lowering interest rates. They have more room to keep going – but they also face more obstacles on the way down.

The biggest ones are their currencies, which don’t loom so large for rich-world central bankers (although US President Donald Trump thinks they should). Emerging-market exchange rates get bounced around as capital shifts in and out – flows that have been amplified by years of cheap money in developed countries. And when money leaves and currencies weaken, it has a bigger impact on prices than in developed countries.

The emerging economies are “at the mercy of the big central banks,’’ said Nariman Behravesh, chief economist at IHS Markit. They have “less room to maneuver.’’ That’s one reason why emerging markets can’t hit the gas too hard. They’re expected to help the world economy with some more monetary easing in 2020. But policy makers in countries like Mexico and Russia, scarred by recent or distant currency crises, are reluctant to slash borrowing costs – even with inflation around the lowest levels in decades.

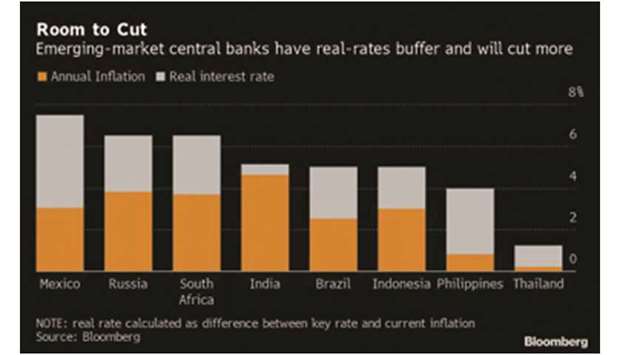

The result is high interest rates, relative to inflation – and strong currencies. It’s an alluring combination for investors struggling to find returns elsewhere.

But it can hurt economies by keeping policy conditions unnecessarily tight, according to Gabriel Sterne at Oxford Economics. The lesson from rich countries, where inflation has consistently undershot, is “don’t be too conservative,’’ said Sterne, who worked at the Bank of England for 20 years. “That’s very hard for central banks in emerging markets, because they’re used to inflation. Having won that credibility, you don’t want to lose it quickly.’

Mexico slipped into recession this year, and Russia hasn’t managed a growth rate above 3% in any quarter since 2012. Both central banks have been cutting rates quite slowly. They have space to go further, according to Goldman Sachs research. They may not use it all.

Economists don’t expect Russia’s benchmark interest rate, currently 6.5%, to fall much below 6% in 2020. By contrast, inflation is already under the 4% target and may be “closer to 2% by the end of next year’’ if the government continues to spend less than it promised, Goldman economist Clemens Grafesaid.

In Mexico too “real rates are still high,’’ he said, and “the cutting cycle is slower than people expected.”

Brazil, in particular, is already there. A new central bank chief surprised traders this year by easing more than expected. But last week he had to surprise them again – by stepping into foreign-exchange markets after the currency hit a record low.

That illustrates the case for caution in the “new paradigm’’ that emerging markets face, according to Christopher Dembik, global head of macroeconomic research at Saxo Bank. “Lowflation is mostly linked to structural factors: ageing, new technology, the level of debt,’’ he said. Rapid rate-cuts won’t address those issues, but “may create some currency volatility.’’ And keeping rates high also leaves room to respond “in case 2020 is the year of the global recession everyone fears.”

In some developing countries, like South Africa, large budget deficits are seen as a barrier to significantly lower interest rates – even when there’s little inflation.

Fiscal policy isn’t much of an issue in Indonesia, which makes it onto Goldman’s list of countries that have high real rates (the policy rate minus inflation) – and thus room to cut. But the central bank spent much of last year raising rates – driven not by inflation, which was flat or falling, but by a currency rout that spread across emerging markets.

The bank has switched to easing this year as the currency steadied, but it’s not expected to get very aggressive. One result: money is pouring into Indonesian bonds.

The headaches that hot money can cause for emerging markets – on the way in as well as on the way out - are getting increased attention at the most august levels of global economic thinking, places like the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements.

At the IMF, new chief economist Gita Gopinath is spearheading work on a new framework of policies that the Fund can recommend to governments. It’s set to include a bigger role for efforts to manage capital flows and exchange rates.

In a May lecture, BIS chief Augustin Carstens said developing-world central banks already “lean against swings in the exchange rate.”

.