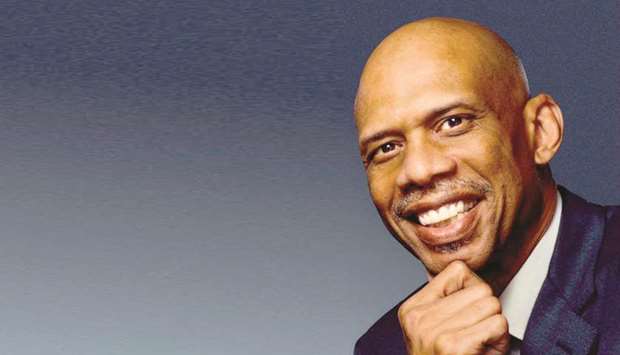

You will be hard-pressed to find photos on the front and back covers of a book that more vividly describe what is written inside than those on Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s Coach Wooden and Me: Our 50-Year Friendship On and Off the Court.

The front cover is a shot of a somewhat rigid Abdul-Jabbar, then known as Lew Alcindor, as a young player at UCLA listening to instructions from John Wooden in 1966. The back photo shows the passage of time with Abdul-Jabbar tenderly grasping the hand of his frail cane-carrying coach, assisting him off the court after a UCLA game in 2007.

If a picture is worth a 1,000 words, “then those two pictures are worth 1,000 chapters,” Abdul-Jabbar said during a recent interview with the Chicago Tribune.

Indeed, those photos show the evolution of the tight relationship between arguably the greatest coach and greatest player in college basketball history. Abdul-Jabbar writes how it was an unlikely bond given the differences in their backgrounds: He is an African-American Muslim from New York City, and Wooden was a white Christian from rural Indiana.

Yet through those 50 years, Abdul-Jabbar recounts intimate details of how these two icons of their sport came together at a most basic human level, elevating their lives in the process.

“Our relationship evolved from being a mentor and father figure to being a friend, a co-traveller in life,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “The evolution was part of the thrill of being with him. It’s what made it really special.”

Abdul-Jabbar, who will appear at 1pm today at the Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Lit Fest, spoke by phone last week from his home in Orange County, California, about his new book. Here’s an edited transcript of the conversation.

What do those front and back cover photos mean to you?

The pictures say so much. When I see them, I question the reality. Who is leading who? It hits home to you, the whole issue of role reversal. When we started out, he was very much the mentor. Towards the end of his life, I had to assume that role for him. I also saw a similar photo of us from that moment (walking off the court in 2007) from behind. It really pulled at my heart. I got teary-eyed.

Do you think the young player in that 1966 photo imagined he would have a 50-year plus relationship with that coach?

When I left UCLA, I had no idea how the future would play out. It was quite conceivable that I wouldn’t return to Southern California to maintain that relationship. I was fortunate to return to play with the Lakers just as Coach was retiring (in 1975). It made it possible to re-establish a relationship on a totally different basis. Soon after, Coach’s wife (Nell, died in 1985), and that accelerated the friendship. We were there to support him. Everything just grew organically.

You write about watching the movie Dillinger at his home shortly before he died in 2010 at the age of 99. Even though it was late in his life, why was it important to you to always deepen the connection?

We had a lot to share with each other. There were things that genuinely interested him. (John) Dillinger grew up less than 10 miles from where Coach lived in Indiana, and the movie visually captured the essence of that time in the Depression. I knew that Coach would enjoy that. It’s what I did with him. It was all about stuff we loved.

Speaking of stuff you loved, people would be surprised to know that you two basketball icons used to watch a lot of baseball games together.

We’re both big baseball fans. I am a National League fan, and he’s an American League fan. We used to have our all-time teams, and argue back and forth. He would talk a lot about managers. I knew nothing about managers. He always had a broader base of knowledge than anybody in any conversation. He had all these facts at his fingertips.

You write about constantly gaining new insights about Wooden. How surprised were you when Wooden revealed years later that he felt intense pressure from the burden of expectations in coaching you and subsequent UCLA teams?

When you think about what he was seeking to achieve, I thought it was all roses. I didn’t pay attention to the part where in order to get to the roses, you have to deal with some thorns. You skip over that in your mind.

You write in the book that the subject of race was “awkward” between you and Wooden, especially at the beginning of your relationship in the mid-’60s. How did his views evolve?

Coach was able to understand how corrosive race could be in black America. It constantly disables in various ways that a white person can’t really understand until they see it happening. He would be on the periphery and he began to notice and hear people say things. A lot of what he heard was really appalling. He came to understand better what we were going through.

What was writing the book like for you?

First, it forced me to remember stuff that happened more than 50 years. That wasn’t easy. Then you go over all the emotional stuff in your life. You let some of those things fade into the edges of your mind. Writing the book brings them all back.

What do you want people to learn about Coach Wooden?

I want people to understand who he really was. Most people think, “Oh, he won all those championships,” and that he is such a wonderful sports story. There’s much more to the story. There is so much more about the real man. —Chicago Tribune/TNS

THERE