Up on stage, Tom Stade lets himself go, shooting the breeze in his now-signature “drunken Canadian” accent. Ever so often, his diagnosis of simple, everyday occurrences or casual observations is couched in humour that’s instantaneously hilarious on one level and pretty poignant on the other.

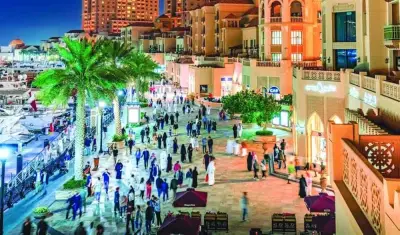

For two nights, last week, at The Laughter Factory gig at Dunes at Grand Hyatt Doha, Stade’s measured performance, laced with devil-may-care irreverence and rockstar coolth, sent the audience into a fit of belly laughs.

You could believe The Independent, which has called him “fresh and endlessly funny… slick, intelligent and sometimes ‘offensive’ stuff leavened by a sparkling charm,” or Evening Standard, which hailed the “Rock n’ Roll comedian” as “absolutely boxfresh; nothing is staid about Stade” — because they both seem to be right.

A regular at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Stade has appeared on Live at the Apollo, Michael McIntyre’s Comedy Roadshow and Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights, among other special shows. He lives with his wife, Trudy, and their children, Mason, 20, and Kira 15, in Edinburgh.

Community caught up with the Canadian stand-up comic — who was on a whirlwind Doha-Dubai tour with comics Justin Moorhouse and Ian Coppinger — to know what goes into being a stand-up star.

As a stand-up comic of considerable experience, what’s your stage plan? Do you prepare a blueprint of your jokes or do you like to riff on things impromptu?

I try and practice the art of stand-up. It’s kind of a mixture of everything. If you want to be one of the greats, whether you get there or not, you will die trying. One of the biggest traits of trying to be one of the great comedians is that you really have to be in the moment. You need to actually enjoy being where you are. Of course, you’ve got your jokes that you have written, which is the skeleton, and then it’s about where you are performing and that’s where the meat gets put on it. You make things up as you go along, like I did here in Doha. I knew what I was going to say but there were a lot of nice little ad libs. Comedy is interesting out here because there are things that could upset people. So you must be very conscious of their feelings. The people here, I’m sure, want to have fun but it’s got to be that kind of comedy and their way of it. It can’t be comedy that’s pushed on by someone else.

So with time, you have learnt to toe the line?

Yes, of course. In my younger days, if someone told me to hold back, I would have gone ballistic and thought I would change the world with my words. But now, I am 46 and I am like, ‘Oh might as well’… ‘It’s okay!’ The fun though is that you are allowed to push something just a little bit as long as you don’t go too far. Even comedy that might be dangerous in the UK is still a little bit dangerous here but not dangerous enough to warrant anything.

What is the feeling you go through when you are up on stage? Tell us about the high.

You mean when you are in the zone, right? So before you hit the stage, everybody says, have a good show, Tom. One day, something clicked in me and I realised I don’t like that phrase, of having a good show or bad. When I go up there, I always think something’s going to happen. Now I am in that stage of my career where even if I do have a bad show, it’s not going to make or break my career or my spirit like it would have when I was younger. When you are on stage, it’s amazing to win people over. It’s the winning people over on to your side that creates the high. You get more of a high being in a show like Doha’s because you have so many different nationalities here. While you are catering to them, you have got to make sure that everything you say, you explain and articulate exactly what you want to say. Then when you do get it right, of course, there’s a high. Just having everybody love you? Come on, man! I think everybody kind of wants that secretly. There’s loneliness, nobody liking you and then there’s everybody liking you. I’d say most people are in the middle. Showbiz gives you that everybody liking zone; maybe not for your whole life, but for a good 20 minutes to an hour, you have everybody liking you. That’s the buzz you are looking for.

Does working on your jokes feels less laboured now than until a few years ago?

I try and write about an hour a day. You work eight hours a day and you work really hard. All I have got to do is force myself to get up in the morning and write an hour. I am not writing for funny, I am just writing my ideas out to keep my mind flowing. It’s not so much to write a joke as it is to be aware that I have opinions on things and I don’t let those go by being quiet. The more work you do without thinking, the less you think. If you are sitting on the desk all day with your computer, a lot of what you are doing is focussing on the computer. If someone asks you what your thoughts are on something, because you haven’t worked that thought muscle, you really don’t know what you think about it. Within those thoughts, what I would do is go to an amateur night club or something, and start riffing. So I start talking in a place that’s a safe environment for me to try that.

Why do you need to that?

That’s because the problem is the bigger you get, the more expectations you carry. So I need a safe place where I can die. Nobody pays 17 pounds and comes to see your show to see you fail. So I go there and work my jokes out. With less structure, you hit it on the head. With a structure, you think you finally found the final punchline. But when I am all free flow, I realise that I will never find a final punchline because any other comedian could walk up to me and say, oh, you should tag it with that. So you get used to figuring out how long you can stay on one topic before the crowd gets bored.

BIGGER